Valve: The Reverse Apple

How a video game company built an empire by inverting the playbook

In November 2025, Valve “unveiled” the Steam Machine – a living room PC designed to bring your Steam library to the TV. Gaming press covered it as news, but what was missing from the headlines was that this is actually Steam Machine 2.0. Valve already tried this a decade ago, and it flopped.

So why try again?

Because Valve learned from that failure. They learned what Apple had figured out years earlier – hardware, software, and services need to, to quote Jobs, “just work” (2011 WWDC).

This isn’t speculation. Take it from Valve co-founder Gabe Newell’s own thoughts on threats to PC gaming:

The threat right now is that Apple has gained a huge amount of market share, and has a relatively obvious pathway towards entering the living room with their platform [...] I think Apple rolls the console guys really easily. The question is can we make enough progress in the PC space to establish ourselves there, and also figure out better ways of addressing mobile before Apple takes over the living room?

(Talk at University of Texas’s LBJ School of Public Affairs, via Polygon in 2013)

Newell wasn’t worried about Nintendo, PlayStation, or Xbox; he was worried about Apple, who weren’t even in gaming then (and still aren’t today).

His solution? Run Apple’s playbook, but do it in reverse.

Trajectories Mapped

To understand what Valve is doing, it helps to see the paths both companies took, and how they mirror each other.

Apple’s Path, Briefly Summarized

Apple’s path to becoming the modern corporate juggernaut that nobody saw coming even 20 years ago needs little introduction: Macs, to portable Macbooks, to portable music (iPods), to iPhones, to App Store, to Everything Else, each step further locking customers into the ecosystem through hardware that “just works”.

Valve’s (Reverse-)Path

Valve was founded by ex-Microsoft employees Gabe Newell and Mike Harrington in the late 90s following their frustration that, among other things, Microsoft was getting outflanked in gaming by startups with a better understanding of how to use the internet. As you might expect from a company with that origin, they started by making video games like Half-Life, Team Fortress, and Counter-Strike.

Steam came in 2003, created for easy management of updates for their games over the Internet (what today would be called a “proprietary launcher”). What Valve soon realized, though, is that they could turn this “cost” into a source of revenue by making their solutions available to other developers, and so came the Steam Store and services (2005). Over time, they built on this, adding features like Managed Matchmaking and Cloud Saves before they took their first crack at hardware in 2015 with Steam Machine 1.0 (aka the Steam Box).

The Steam Box… didn’t do so hot. We’ll get to that.

After that, the important points in the timeline to note for this narrative are the release of the Steam Deck (a portable PC gaming device, perhaps most analogous in function to the Nintendo Switch) in 2022, and the instigator for today, the announcement of the Steam Machine (2.0) for 2026.

For a snapshot of how Steam stands today:

Regularly peaks at ~41MM concurrent users on weekends: https://store.steampowered.com/stats/stats/

Note: that’s concurrent users, not distinct users over the course of the weekend. As a global platform, it’s absolutely the case that distinct user count in a 24 hour time period is higher than that.

While we don’t have any official recent Monthly Active User (MAU) numbers, Valve gave a figure of about 132 MM at the end of 2021.

If we scale that using the ratio of peak concurrent users then vs now, that gives an estimate of ~200MM MAU (though this is very rough)

A couple of contextual comparisons:

Netflix has ~300 million subscribers, about 100 million of whom are on the ad-supported tier.

Uber reported ~190 million MAPC (Monthly Active Platform Consumers, i.e. “people who took a ride or bought Uber Eats delivery”) for the most recent quarter.

eBay has ~135 million “Active Buyers” (defined as an account that made a purchase in the last year).

Learning from Steam Machine v1/v0

Many may be surprised to learn that the Steam Machine being released in 2026 is actually Steam Machine 2.0. Valve, for its part, seems to be tacitly trying to memory-hole the earlier model; essentially none of the messaging about the new release brings up the fiasco from a decade prior. However, it’s clear that Valve has internalized a lot of the failures from that affair:

Failures of 1.0

Underbaked Supporting Software:

It’s a perceived truism in the games industry that platform exclusives drive platform adoption. While I think this is on the whole significantly overstated, and it seems like the industry itself might be coming around on that, it’s hard to deny that the fact that many major games just didn’t run on the original Steam Machine’s software could hardly be called a selling point:

Probably the biggest issue holding back the Steam Machine at launch was the [...] fact they only run games that have Linux versions. Three of the platform’s biggest titles in recent years: The Witcher 3, Grand Theft Auto 5, and Metal Gear Solid V, still aren’t supported, which is a big problem for a machine aimed at gamers.

(The Steam Machine: What Went Wrong | TechSpot, 2017)

Even looking at the games that were supported, they performed worse on SteamOS than they did on Windows… which ties into the next point:

Self-Cannibalization:

Steam Link, launched in 2015, allowed owners of (sufficiently powerful) PCs to stream games to the TV over your (hopefully uncluttered) WiFi network at a lower price point.

What did that mean? You had two options:

Purchase a new machine that cost anywhere from $500 to thousands and hook it up to your TV; or

Purchase a little stick for $50 and use the PC you probably already gamed on before all this as a local server for your games. You know, that PC running Windows, which apparently runs those games better anyway.

Gosh, I wonder which one consumers would want? /s

Unclear target consumer

For this one, I’m just going to quote directly from another publication that ran a postmortem article on all this about a decade ago:

“We started thinking, ‘Hey, you know, we’re actually creating a middle-tier niche for this at this point,’” says [Michael Hoang, marketing manager @ iBuyPower]. “You have your console, you have your PC gamers, we’re right in between. We’re right in the middle where no one can really claim which one this is. So now we’re creating a new demographic that has never been created, so we have to do everything from the ground up at this point. And it was very, very hard to convince people, well, do I want to be a PC gamer? Do I want to stick with just being console? Or this new thing in the middle.

(What happened to Steam Machines? | PC Gamer, originally published 2017, re-published 2018)

Landscape of 2.0 (and the earlier Steam Deck)

How does this compare to the situation in 2022 (with the Steam Deck) or 2026 (Machine 2.0)?

Matured Software Ecosystem:

On the back of years of testing/improvements and launch of the Steam Deck, the Proton gaming compatibility layer for Linux means even some brand new games can, out of the box, often “just work” on SteamOS without tuning. ProtonDB tracks compatibility, and counts 7000+ games that are verified to work as well or almost as well as on Windows, and when sorting games by popularity on Steam (i.e. the main platform), you have to pass more than 40 at time of writing before you get one that isn’t at least “Gold” rated.

Death of Steam Link

While the software still technically exists and is usable, the hardware is dead, and even the software has “better” open source alternatives that are recommended by the community as the go-to solutions (ref: Moonlight/Sunshine).

Target consumer

This one is less clear; while (at time of writing) the pricing of Steam Machine 2.0 is not confirmed, it has been stated that it won’t be sold at a loss despite only having the hardware to be performance-competitive with current-gen consoles (which are sold at a loss, and so would be expected to be cheaper). At a glance, it seems like Valve is setting themselves up for the same “are we PC gamers, console gamers, or something in the middle” question all over again.

However, there’s an argument to be made that, if the Steam Deck is the iPhone of gaming, then the Steam Machine is the iPad – an interoperable, friction-free extension of the software to a new form factor, built to fulfill a complementary purpose to the Deck. Moreover, “a slightly more expensive console” is an easier sell when you can also play your games on the go with the Steam Deck, in that (again) it centralizes your library.

The Biggest Learning from 1.0

Returning to the earlier-mentioned PC Gamer post-mortem:

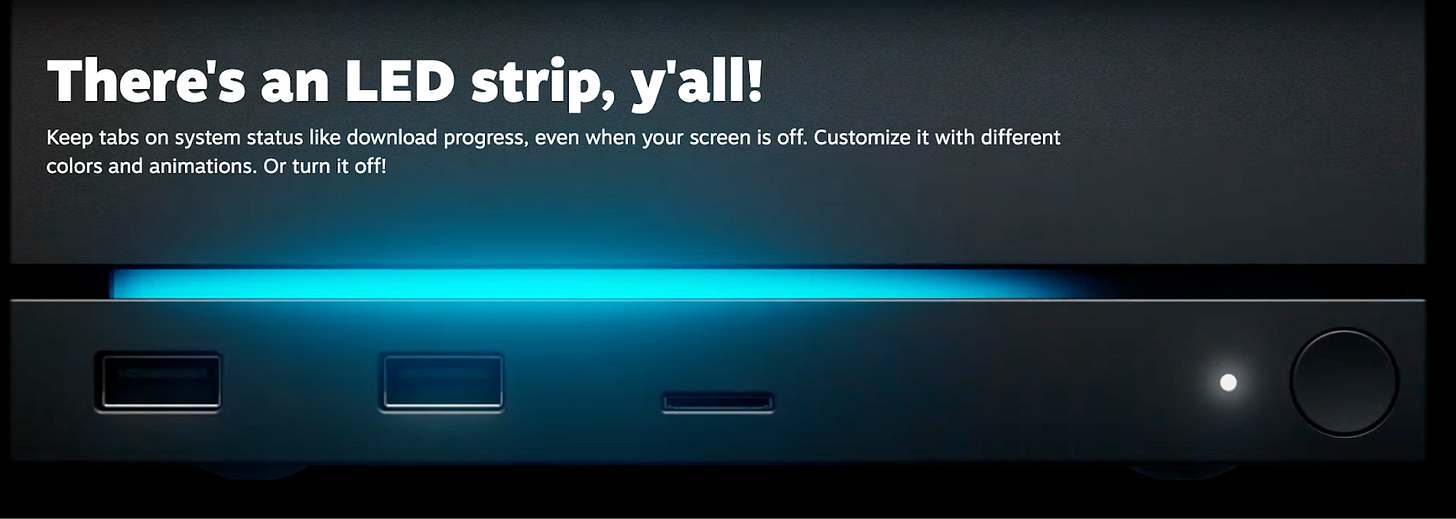

What’s the best thing to come of iBuyPower’s SBX? The LED strip, says Hoang, which looked really nice.

Now, taking a look at the Steam Machine store page:

Jokes aside, I think Valve’s biggest takeaways from the debacle that was “Steam Machine 1.0” was that, for their vision of hardware to make sense as a customer purchase, it need to be smooth; they couldn’t just ship an MVP and build on it later, or rely on third-party partners specialized in hardware to build the rig while they made the software and hope that the two would meet in the middle. No, they needed to control the hardware, the software, the interface, the messaging, everything.

They learned that it all needed to “just work, seamlessly”.

Deeper Parallels

The parallels aren’t only in their trajectories and ultimate product offerings, though. A deeper examination of what makes these companies unique and valuable reveals more similarities, which is perhaps unsurprising considering that they are both also very, very successful.

Philosophy on Piracy

Both Jobs and Newell view(ed) digital asset piracy as a problem of availability and convenience.

Jobs:

We believe that 80 percent of the people stealing stuff don’t want to be; there’s just no legal alternative. So we said, Let’s create a legal alternative to this. Everybody wins. Music companies win. The artists win. Apple wins. And the user wins because he gets a better service and doesn’t have to be a thief.

(Esquire Magazine Interview, 2003)

Newell:

“We think there is a fundamental misconception about piracy. Piracy is almost always a service problem and not a pricing problem,” [Newell] said. “If a pirate offers a product anywhere in the world, 24 x 7, purchasable from the convenience of your personal computer, and the legal provider says the product is region-locked, will come to your country 3 months after the US release, and can only be purchased at a brick and mortar store, then the pirate’s service is more valuable.”

(2011, proxied quote from The Cambridge Student via The Escapist; thanks to teddyh on HackerNews for digging up the archive link for TCS!)

This take by Newell is borne out by results, as he goes on to explain:

“Prior to entering the Russian market, we were told that Russia was a waste of time because everyone would pirate our products. Russia is now about to become [Steam’s] largest market in Europe,” Newell said.

While Jobs is providing an optimistic view on people’s morals and Newell is looking more clinically at overall value like an economist, they both point at the same underlying idea, i.e. “users will pay for a good experience”. We return again to Jobs’s famous refrain of “it just works” – and customers will pay you when it does.

Creating Cults

When Steve Jobs died in 2011, people left flowers at Apple stores. When Gabe Newell so much as posts on Reddit, threads debating what happens to Steam without him rack up thousands of upvotes and comments. Both companies have fanbases that behave less like customers and more like congregations.

Even after almost 15 years of Tim Cook at its head, when you think “Apple”, you think of the iconic image of Steve Jobs looking directly at the camera with his hand on his chin that became the cover of Walter Isaacson’s biography. Jobs’s ideas around design as the lodestone of product development, his relentless focus on the customer experience, his love for simplicity – all of these are written into Apple’s very DNA and are the exact things customers love about their products.

While the general public might not recognize the name, Gabe Newell is the same in gaming circles. One need look no further than even reactions from those fans when Gabe Newell questions his own celebrity treatment. And just like Apple, this cult-like veneration extends to the company itself – despite having been almost 20 years since the last mainline entry in the Half-Life series, memes and (half-?)jokes about “Half-Life 3 when” have not died down, and when Valve announced a prequel VR game in the series due to release in 2020, the trailer racked up 10 million views in less than 24 hours… and, of course, prompted a fresh wave of “Half-Life 3 when?”

This phenomenon of fandom cannot be viewed as anything but a competitive advantage. Both companies have audiences that will literally hold off on buying things in case their “preferred” creator might enter the space, and watch their every move like hawks to determine what to “get hype” for.

Divergence

Valve and Apple do differ in one major respect, however: Valve seems staunchly unwilling to pursue any explicit, strong lock-in.

Unlike Apple hardware, the Steam Deck does not need to be jailbroken in any way, and Valve explicitly provides a guide for how to go outside their ecosystem (and potentially brick your very expensive game machine). The messaging for the Steam Machine 2.0 seems equally “free”:

Yes, Steam Machine is optimized for gaming, but it’s still your PC. Install your own apps, or even another operating system. Who are we to tell you how to use your computer?

Aggregation Theory and Valve

A useful lens for understanding the dynamics at play when talking about Valve/Steam is that of Aggregation Theory.

Aggregation Theory is a model and way of thinking about businesses enabled by the Internet and digitization, conceived and coined by Ben Thompson of Stratechery. Thompson labels “Aggregators” as businesses having three core characteristics:

A Direct Relationship with Users

Negligible Marginal Cost for Additional Users

Demand-Driven Markets with Decreasing Acquisition Costs

Is that a mouthful? Yes, and the big words hide a lot of complexity. For those who want to really understand it (something I encourage, as I think that a lot of both the successes and failures in recent times of tech companies, whether in product strategy or regulation, come from a misunderstanding of these dynamics), I’d encourage going to the source and spidering out to related, mentioned articles (Thompson does such a great job at linking between his pieces that I’m tempted to provide a quasi-TVTropes warning first):

However, for our purposes, I think we only need to engage with the concept at a high level.

Consider AirBnB (which might not initially seem like an aggregator), an example Thompson himself brings up often. Homesharing wasn’t a new concept that sprung fully-formed from Brian Chesky’s forehead; couchsurfers and foreign exchange students engaged in it for decades. What AirBnB did was aggregate demand – they made it trivially easy to find a nice place to stay. Once enough travelers were searching on AirBnB, hosts “had to be there”. Once enough hosts were listed, why would travelers look elsewhere? The platform became the default not by being the only option, but by being the most convenient.

In this regard, Steam works the same way.

Valve’s Current Position

Steam is inarguably an aggregator, and arguably close to the platonic ideal of one:

Direct Relationship with Users – As a customer, you make an account with Steam to activate products managed through it. While you don’t have to give them your payment information, it’s certainly more convenient to do so. It would almost require active commitment to avoid doing so: you’d have to exclusively buy game keys from other retailers, handle any and all in-game purchases directly with the game creators (if even possible), and deny yourself the ability to buy anything during the ever-rotating Steam Store sales that often feature deep discounts on a wide swath of games.

Negligible Marginal Cost for Additional Users – Steam is a digital storefront, so yes. Additional users are just an O(1) addition of rows in a few database tables. And while Steam obviously incurs some transaction costs when users buy things, who doesn’t pay the gatekeepers of Visa and Mastercard?

Demand-Driven with Decreasing Acquisition Costs – Steam is practically self-sustaining on both sides of its market. Customers not already on Steam are liable to wind up there by accident just buying a box copy of some game or another. That mass of users attracts developers, both small and large, even ones that left believing their fans would follow.

As a platform, Steam is also increasing lock-in:

SteamVR serves as the “platform” for VR development, driven by customer demand for Half-Life: Alyx, with the Steam Frame as the first-party platform (alongside already-existing VR hardware options like HTC Vive or Oculus Quest)

The Steam Deck functions as the “iPhone for PC gaming” (direct quote from GabeN)...

And now comes the Steam Machine to complete a “hardware trifecta” to mirror the iPad.

All of these hardware offerings are undergirded by the self-lock-in of users who have a significant portion (sometimes a supermajority) of their gaming libraries in Steam, which is (currently) non-transferable (c.f. iTunes/App Store/iCloud)

In this light, the parallels to Apple are hard not to see, but Apple “integrated forward” – they created great hardware that brought customers to them first, then slowly built the pretty walls around the garden users had entered, even as the garden itself expanded into new domains like mobile and watches.

Valve, by contrast “integrated backward” – they created the ecosystem first, offering both customers and developers amenities like managed updates, cloud saves, mod hosting, and content distribution networks before creating their own first-party hardware that leverages all that work.

“The Metaverse”

A core contributor to the success of both Apple and Valve is that they both grew naturally (if in inverse directions):

Apple went from PCs, to laptops, to portable music, to smartphones as a generalization of their learnings from ‘portable music’, and finally to the modern ecosystem of software & peripherals (watches, headphones, VR).

Valve started in video games, then made a game launcher/update manager for their games, then offered that update management service to other developers with a storefront before finally getting to the hardware.

At each step, both companies responded to real market demand and simply did a better job at capturing that demand through UX. You can even see the proof by contradiction: The Steam Machine 1.0 shows where they perhaps moved too early or chased illusory demand, and a similar story may be repeating itself with Apple Vision.

It’s instructive to contrast this with Facebook’s “all-in” pivot to metaverse. At first blush, there are significant parallels to Valve, in that both Zuckerberg and Newell had built their fiefdoms in the lands of other empires and were trying to “escape their jailers”:

Newell was trying to get out of “Windows 8 jail” and the potential that Microsoft might smother their business with expansion of the Xbox business.

Zuckerberg wanted to leave the Apple/Google app platforms of iOS and Android, where their decisions around privacy could kneecap FB profits (ref: iOS’s App Tracking Transparency initiative), and run his own platform from which to derive value (or, being more cynical, collect rent).

However, it’s hard to imagine a bigger gap in outcomes between the two. Looking at the result of Facebook’s metaverse efforts in December 2025:

A stagnant Quest store/ecosystem

70 billion dollars in losses associated with the pivot

4 years invested for no meaningful revenue growth

Planned 10-30% cuts to Metaverse

Perhaps most depressingly, investors drove stock 3-5% higher following release of news, indicating they were also fed up with this nonsense.

Why? Well, Zuckerberg’s big pivot was completely unbacked in demand, whether from customers or enterprises, to match the scale of the investment he decided to fling at it. Moreover, it had an at-best tenuous connection to the core competencies that Facebook had developed in scalable software, social networks, and advertising. Zuckerberg often talked about how everyone would interact with virtual avatars while on the go or in meetings across timezones or what have you, and how that tied into Facebook’s mission of connecting people, but as the saying goes: if you need to explain the joke, it isn’t funny.

Visions Of The Future

All of this analysis begs the question: What sayeth the crystal balls?

Aggregation Theory

If we’re looking at things as Aggregation Theorists, continued near-total monopoly is the obvious end result, absent significant developments:

What is important to note is that in all of these examples there are strong winner-take-all effects. All of the examples I listed are not only capable of serving all consumers/users, but they also become better services the more consumers/users they serve — and they are all capable of serving every consumer/user on earth.

(Aggregation Theory | Stratechery, 2015)

Competition is difficult once a big aggregator has emerged, even for deep-pocketed incumbents. One need only look at famous examples like Yahoo or Bing vs Google, or Walmart vs Amazon. Epic Games already tries to offer competition in digital storefronts by leveraging the breakout success of Fortnite to launch their Epic Games Store, with a more generous revenue split for developers and the backing of Tencent to buy up store exclusives (even if timed only) by flinging money around. However, 7 years into the experiment, these terms don’t seem to have resulted in any significant upturning of the apple cart.

Ben Thompson (of Stratechery) suggests that traditional platforms might offer an avenue by which competition can rise, looking at Shopify vis a vis Amazon. However, it’s unclear what “a platform approach” might look like as competition in the context of gaming here. Indeed, if you asked me what an extensible platform might look like in gaming, I’d say that Valve are, themselves, operating closer to a platform than a straightforward aggregator by making Proton/SteamOS free for other companies to use and potentially develop on top of (ref: Lenovo Legion Go S and ASUS ROG Ally as competitors to Steam Deck that can use Proton/SteamOS (though by default ship with Windows 11)).

So, if the traditional mechanisms of the market find no purchase, might we look elsewhere?

Regulation

Antitrust is also hard, at least based on dominant US thought. Those who know me personally will know that I’ve long railed against Robert Bork’s consumer welfare standard for evaluating mergers and antitrust.

I’m hardly the first or alone in this – perhaps most notably, former FTC Chair and current Mamdani transition team member Lina Khan first made her name penning “The Amazon Antitrust Paradox” as a direct refutation of Bork’s ideas. However, despite some recent small shifts suggesting that the climate may be changing, it remains the default standard, and considering that users specifically choose to go to the aggregators due to the benefits they offer (whether on price or quality), consumer welfare seems unlikely to find any justification for action.

However, there are potential avenues in forced service interoperability and data portability. In short, the idea is that regulations can mandate that platforms of sufficient size have to allow other services to be able to integrate in some (perhaps standardized, limited) ways with the incumbent giants. This is an idea that’s already being trialed by the EU via the Digital Markets Act (DMA) for messaging (even despite some real and valid technical concerns), and it’s also being partially (voluntarily, seemingly) rolled out in music streaming apps (specifically between Apple Music and YouTube Music). While it’s early days, if these initial forays work without significant snags, it may embolden other legislatures to make similar moves that ultimately wind up hitting Steam, forcing it to cooperate with EGS in some way like allowing Steam users to take their validly purchased games to EGS if they want.

Enshittification

Cory Doctorow’s pithy (if crude) term and model, which posits that platforms are eventually incentivized to ruin the experience for everyone on them in search of profit, might credibly be argued to be the end state of all platforms controlled by profit-seeking entities. And arguably, Steam has long since been “enshittified” in some regards. The deluge of games on the store that are approved for release without quality control has led to cheap, buggy messes or even outright malware finding their way onto customer machines. This is not a new problem, either, with industry analyst and pundit James Stephanie Sterling having coined the term “the asset flip” in 2015 to describe a problem that has only grown in scope since.

However, while that criticism might hold water for some industry professionals, power-users, and gaming enthusiasts who want to find “hidden gems”, for the average consumer, Steam generally remains a good experience for discovery, purchase, and library management.

Looking forward, as a private company that is majority owned by Gabe Newell himself, Valve is not as vulnerable to the kinds of short-term shareholder pressures that public companies or heavily venture-funded companies like Facebook/Bytedance face. While that alone is no guarantee, the combination of profitability, patient capital, and founder control may stave off the specter of enshittification for some time yet, at least while current leadership remains.

That is, however, also why, as mentioned earlier, many fans fret about what might happen to Steam and Valve in the absence of GabeN.

Technological Advancement

While it’s hard to say what direction technology might go in the future (who could’ve predicted in Oct 2022 that the US economy’s growth would hinge on LLMs?), there is one obvious avenue that may pose a threat: Cloud Gaming is only getting better.

Surfaces like Xbox Cloud Gaming or Nvidia GeForce Now are currently only either technological solutions that allow access to existing libraries (e.g. Steam or EGS via Nvidia GeForce Now) or Netflix-esque “subscription packages” for pre-selected games. However, there’s no technological reason preventing these providers from attempting to fight with Steam as a digital storefront; Google Stadia already tried this in a form, and while that service was eventually shut down, there’s nothing to suggest that the idea itself is inherently unworkable. If these services want to become “the Uber for gaming”, a storefront may eventually be a necessity; many of these services already have experimented with messaging of “pay-as-you-go” for gaming hardware, gesturing at a future where you never have to worry about hardware compatibility or drivers because it “runs in the cloud”, all of which is reminiscent of the “you won’t need to own a car, a self-driving one will just come pick you up” vision pitched by Uber or Tesla in years past.

Conclusion

If you were to ask me where things likely go from here, I’d say Valve will remain the much-beloved de facto king of PC gaming for the foreseeable future. This isn’t because they’re inherently more talented or virtuous, but because the factors for decay just aren’t there. They’re private, they’re profitable, and (if nothing else) they’re patient (Half-Life 3 when, GabeN?). There’s no strong incentive for them to enshittify.

The parallel to Apple isn’t perfect, though; the companies have taken different directions in some aspects. The more open approach Valve has taken with Proton and SteamOS is perhaps the most obvious, and I personally consider that to be a strength, especially in the context of regulation. However, there are other differences as well, and the one that stands out to me is in social infrastructure.

If I say “blue and green bubbles”, the direction I’m pointing at should become clear. Apple has leveraged their branding and dominant position (at least within the US) to elevate the iPhone to a status symbol, and in so doing has created network effects through iMessage and Facetime that further keeps their customers within their ecosystem in a way akin to traditional social networks (“I can’t leave Facebook; that’s how I keep in touch with my high school buddies!”). By contrast, while Steam does have chat and groups and forums and other social features, calling them “anemic” might be generous. When it comes to PC gaming, while most things make you think Valve and Steam, if you talk about social lock-in, it’s Discord that comes to mind, and that’s a chink in the fortress Valve has built.

The question is, will social infrastructure be as critical in gaming platform lock-in as it has been to mobile? If Apple’s trajectory is any guide – iMessage didn’t seem critical until it revealed itself as one of their strongest moats – owning the social layer may matter more than is obvious today.

\0